Are you considering going on an artist residency but aren’t sure if it’s a good idea? Maybe I can help you sort through your thoughts. I have been on eight different residencies thus far, and have a range of experiences to draw from in my reflections. Since some of what’s going to come up might make it sound like I dislike residencies, let me just state right at the beginning that I love being an artist-in-residence! I do, however, think it is very important to fully think through your residency plans to make sure that you, too, have great experiences.

1. Have you been on any other artist residencies before?

If not, you may not be sure if residencies are for you or you may be sure… but nevertheless hate it when you get there. All but one of my residencies (I’ve been on eight) have had artists apply, arrive, and flee early. This is even more surprising when you consider that typically residents have already purchased round-trip tickets, have made rental car arrangements, and other financial decisions that mean the cost of leaving early can be very expensive indeed compared to just sticking it out once already there. Here are some of the reasons I’ve heard as to why people have left early:

They thought the residency would inspire them during a period of creative funk, but once they arrived, unpacked, and sat down in the studio in front of an empty easel or table, they feel blocked even more intensely.

They applied to a very isolated residency with few people around, and while this fact was disclosed and they thought they were comfortable with the isolation, in reality it was very scary and they couldn’t handle it.

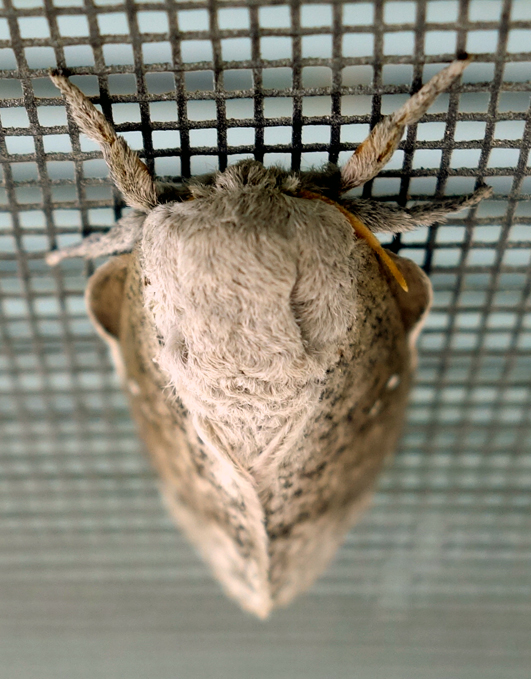

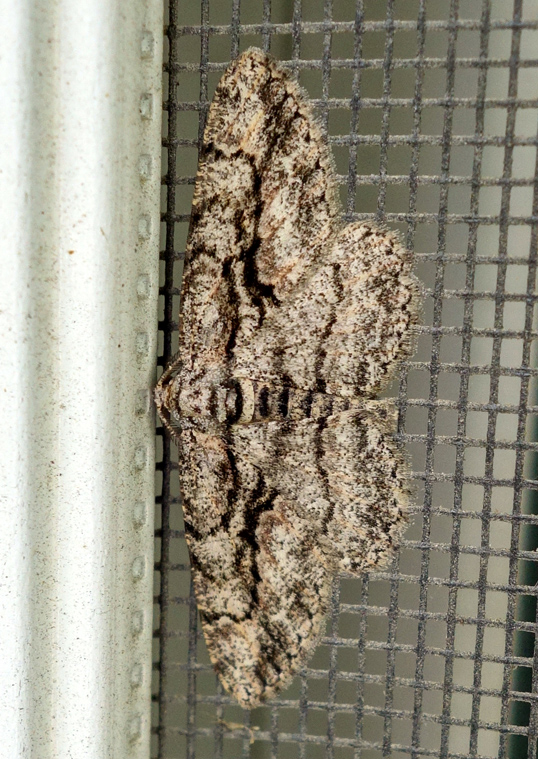

They applied to a rural residency - out in nature - thinking romantically of strolls through a forest. They left when they discovered that insects including mosquitoes, flies, spiders, beetles, and ants regularly got into their living spaces and they could hear large animal noises outside at night.

They either through lack of research or misleading advertising copy were physically unprepared for the residency. Several that I have attended required twenty-minute steep climbs up a mountain. One had only a sawdust toilet. Several had no hot water. A couple required boiling the water to make it potable.

There was no reliable internet or cell phone connection on the residency site and while they knew in advance about that, they didn’t fully appreciate how much that changed their comfort levels and/or process.

If you’ve never been on a residency before and want to try it out, I recommend doing a short domestic one to minimize costs and dip your toes into the experience before taking on a longer-term or international one. Even if your residency is fully funded (more on this in question 5 below), it is still costly to do a residency as many fully-funded ones nevertheless don’t pay for travel costs as well and there are often associated charges that rack up (taxis to airports or airport parking, higher food costs due to unfamiliar and sometimes restricted setups at the residency, costs of renting a car or of public transit, paying someone to look after your pets/plants, etc). Dipping your toes in can let you begin to get a taste for whether or not you like them and what your preferences would be moving forward.

If you have been on a residency before, you have probably started to form some opinions about them - the importance (or insignificance) to you of location, number of other residents, studio setup, exhibition space, duration, provided amenities, cost/payment, and application fees are all factors to consider.

2. What are your primary motivations for going on residencies? Will the one you’re considering satisfy those?

I like to escape from the familiar patterns at home that take away time making art - hanging out with friends, going to the gym, hitting up the local farmers market, etc - and really focus on artwork production. I enjoy exposure to new and different ways to live, and love immersing myself in new ecosystems.

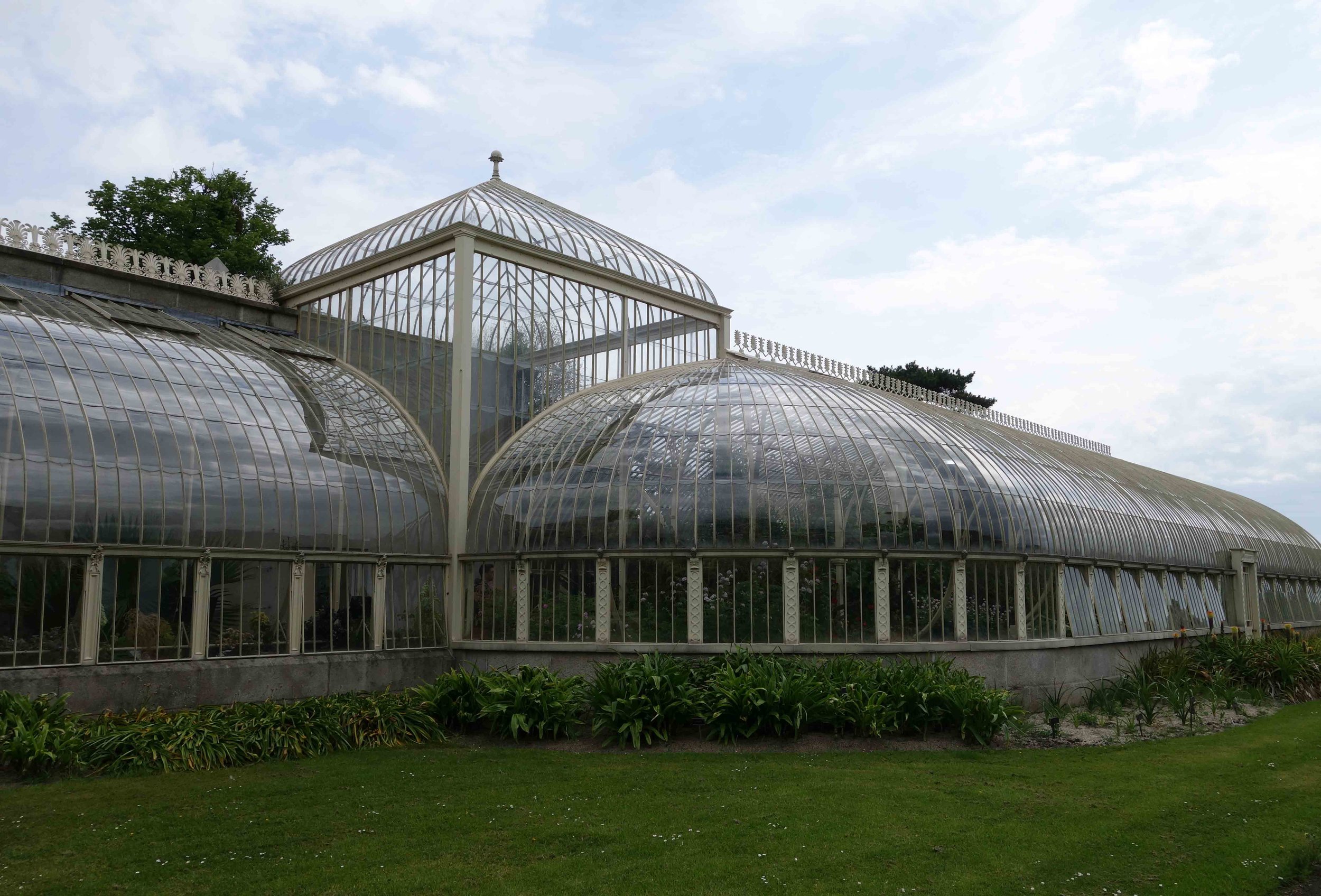

Residencies not only build my professional standing through artwork generation and exhibition but also improve my teaching. Attending residencies has allowed me to expand my network of artists, galleries, and opportunities, which I can then share with my students through guest artist lectures and exhibitions in my institution and exhibition opportunities for our students. Residencies also facilitate conversations with other art professors and instructors, expose me to new classroom exercises, and allow me the opportunity to visit world-class museums with art collections that I can reference in the classroom.

I know why I go on residencies and get a lot out of attending them. You may not have the same desires for going on one, though, and your motivations may or may not be realistically achievable in the residency you’ve chosen. For example, if you want to see other artists’ studio practices, applying to a solitary residency (I’ve been on four where I was the only artist in residence during my stay) is a bad idea.

Here’s another example of thinking through your motivations: I speak Spanish proficiently and therefore attend residencies in Spanish-speaking places often. More often than not my fellow artist residents have little to no Spanish proficiency (they were allowed to fill out the application to the residency in English), and they are regularly surprised by how limiting not speaking the local language can be both in their day-to-day existence and in their arts scene engagement, and several felt somewhat dissatisfied in the end by that limitation.

3. Have you researched the residency, the town or city the residency is in or outside of, the country, the weather that time of year, the crime level, and so forth?

It is really important to be educated beforehand about what you might experience, particularly if your destination is international. For instance, I knew that there was limited electricity in the Peruvian Amazon residency I attended and I brought a very useful solar light along with me. I also got a few vaccines - yellow fever, for instance - in advance of heading off to that residency and brought some anti-malarial medication along just in case. You should brush up on at least a few phrases in whatever the primary language is - I learned some French and Portuguese prior to my residencies in France and Portugal and they both proved quite handy. You’ll possibly need travel adapters, or even voltage converters, for your electronics. Are you going to rent a car? Will you be driving on the side of the road that you’re used to? The list goes on, and varies tremendously.

4. Have you reached out to former residents to get a better idea of what the residency will be like?

I really recommend this; do research on who has previously attended the residency and read any of their blog posts about it, and perhaps even shoot a few of them emails asking for their advice for you. Even if they loved it, they may have great packing advice, and if there were points they didn’t like so much that’s helpful knowledge to have when you’re making your own determinations about attending.

5. How much is the residency you’re thinking of attending charging and/or providing you in terms of a stipend? Are there any donation, workshop sessions, work hours, or other requirements associated with the residency?

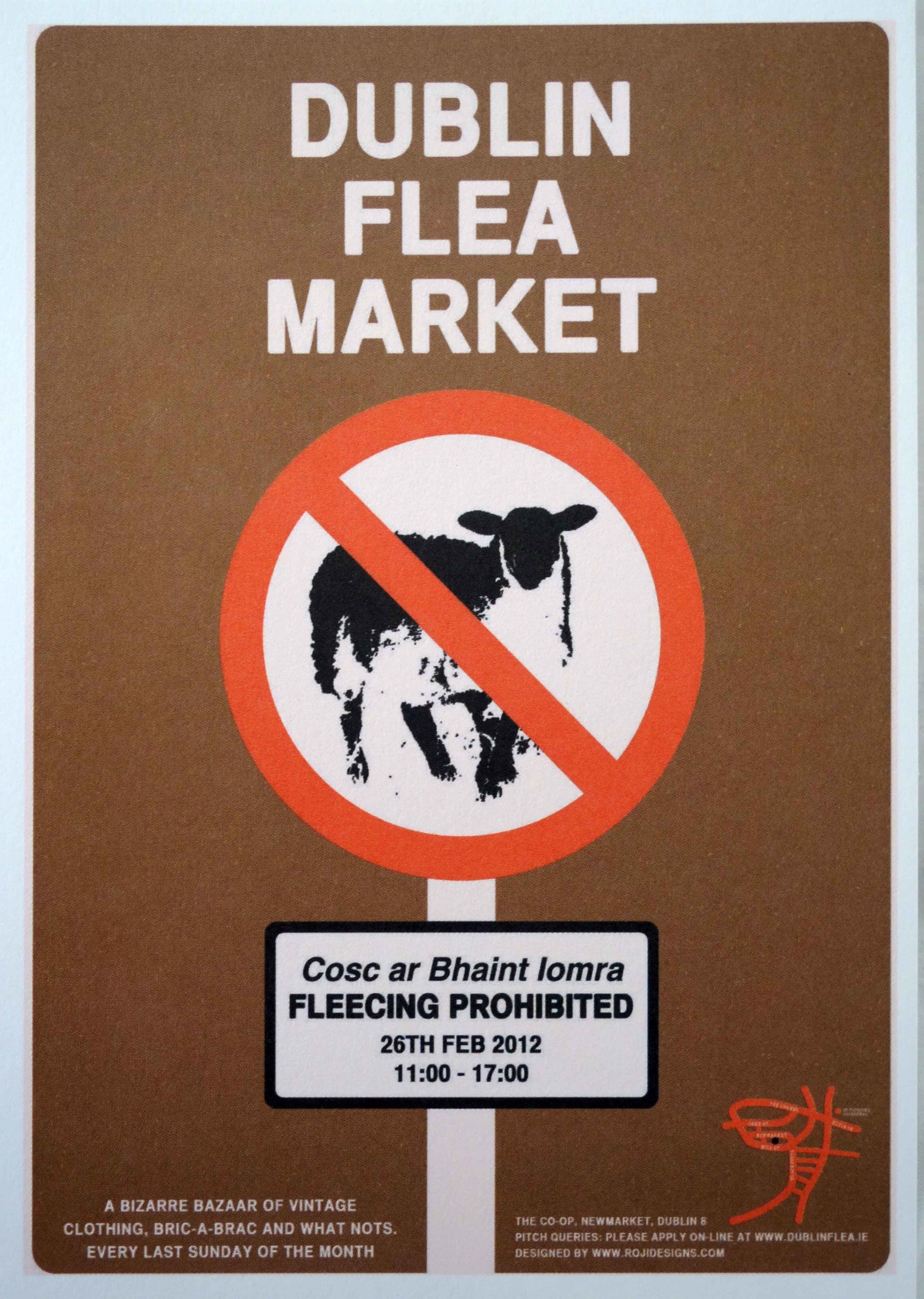

There are a lot of amazing residency opportunities out there… and then there are more than a few that are clearly money-making operations that are perhaps better understood as a vacation-in-disguise rather than a work arrangement. There’s absolutely a place in the world for that latter type, too, but you really want to go into your residency understanding which it is and whether that serves your purposes.

I only attend places that are “split-cost” or “fully-funded” residencies. Split-cost residencies share the cost with the artist; they are not free but rather partially subsidized. There is a fee you will pay to the program that covers your share of the housing, studio space, marketing, exhibition space, and other needs in a “split-cost” residency, but the host organization is also covering part of the cost. Fully-funded residencies have no costs to attend (though most don’t pay for your travel to get to and from the site) and some even have stipends. Most that have stipends do have some compensating task you complete for the host organization, however - it could be donating some of the work you make during the residency, or leading a workshop for a local audience, or contributing to the overall property (gardening, cleaning, cooking for the group, etc) in a certain number of work hours per week. Be realistic about what you are willing and able to do!

I have several reasons why I only attend split-cost or fully-funded residencies. Most importantly, I think that having the host organization bear some or all of the cost makes them more selective of their residents and more professional in their residency requirements and structure. It also looks better on your resume or CV! I also find that split-cost or fully-funded residencies are what fit into my budget. You might reasonably then wonder why I don’t only attend fully-funded residencies - the answer is that there are only a few international residency opportunities that are fully-funded, and of those, even fewer that fit into my summer availability. Since my artwork has an ecological focus, having an international studio practice is important to me and worth a reasonable shared cost to me.

You may be considering a “full-cost” residency, however, where you would be paying for everything at tourist/consumer prices. If so, just make sure you get your money’s worth and consider any amenities offered that may make the price point more reasonable, like covered meals, transport, guest availability, and so on. Also note that many full-cost residencies have a more service provider-customer relationship rather than an arts program-artist relationship, and that does impact the tenor of the residency. A number of full-cost options also don’t actually require/expect that you make artwork while there, which some people enjoy as it takes some pressure off but can also somewhat defeat the purpose of going on a residency as opposed to just a vacation in a local hotel or Airbnb.

6. Is the specific residency you’re considering actually a good fit?

This question sort of loops back around to the points brought up in several of the other questions. Be honest with yourself and introspective, and really think through if the residency will be a good fit. Will there be any other residents on site while you are there? Will you have to share a room? Will you need to be comfortable staying in a co-ed space? Will you be lonely? Will you have internet access? Is there a kiln? Will you get to exhibit? Is the location one you want to be in for the length of time of the residency? Will you feel safe? Will you have easy transportation options? Can you cook for yourself?

Again, I know that I may sound like I think residencies are terrifying, unproductive experiences - and while on a rare occasion they unfortunately can be, I’ve been fortunate to have in general benefited personally and professionally from the ones I’ve attended. But the takeaway is that not all residencies are right for all artists, so doing your homework and reflecting on your own motivations and needs will go a long way towards ensuring that if you do attend a residency, you have a great time and perhaps even make some new lifelong friends!

Finally, here are some of the biggest residency aggregation sites to browse through to find your first, or next, residency!

Res Artis

TransArtists

CaFE